Le parole di Midirama, uno dei protagonisti del Festival Bogotrax, descrivono un’esperienza unica e intensa, simbolo di un’incredibile fusione tra musica, arte e impegno sociale. Ma questa non è solo la sua storia. È una testimonianza di come la musica possa attraversare confini fisici e mentali, portando speranza e connessione anche nei luoghi più oscuri e oppressivi.

Midirama, insieme a altri artisti come El Gran Latido, Fufu, Baptiste, Seppuku e Rach, ha attraversato le porte della prigione per portare la sua musica e il suo messaggio di solidarietà agli internati di Carcel Distrital. Ma dietro questa missione di intrattenimento c’è molto di più: la volontà di rompere le barriere tra le persone, di condividere momenti di gioia e di riconoscere l’umanità in chi spesso viene dimenticato dalla società.

Nell’editoriale che segue, esploreremo le esperienze di uno dei DJ presenti, immergendoci nelle sue emozioni, nelle sue sfide e nelle sue speranze. Attraverso la storia di Midirama, scopriremo il potere trasformativo della musica e l’importanza di mantenere viva la fiamma della creatività anche nei luoghi più bui. Benvenuti in un viaggio dentro le mura della prigione, dove la musica techno diventa un ponte verso la libertà e la rinascita.

Visualizza questo post su Instagram

“Febbraio 2024, Bogotà, Colombia. Ecco le foto promesse dalla prigione colombiana durante il Festival Bogotrax. Mi sono svegliato presto quella mattina, dopo una lunga notte di festa per strada, per incontrare gli altri fuori dal carcere quando l’audio per El Gran Latido era già stato settato. La procedura di ingresso è stata rigorosa, dobbiamo consegnare tutto tranne le cuffie e la chiavetta USB, mentre veniamo controllati da metal detector e dall’unità cinofila.

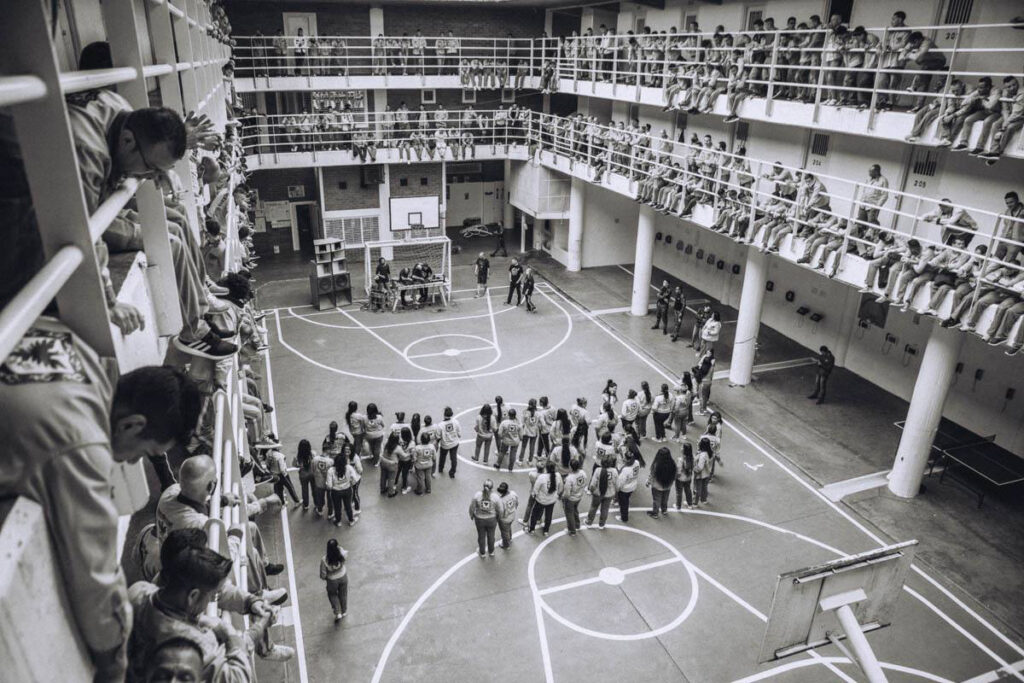

Una volta dentro, l’atmosfera era intensa, con un mix di caos e eccitazione. Ho visto donne affacciate dai piani superiori mentre assistevamo a breakdance e freestyling da parte dei detenuti, con MC Baptiste che alimentava l’umore. Il mio set è stato breve ma intenso, e ho condiviso la mia maglietta con la folla, un gesto apprezzato da tutti. Alla fine, mentre uscivamo, sapevo che alcuni sarebbero rimasti lì per molti anni. Fuori, ho preso un profondo respiro, pronto per nuove avventure con Bogotrax.”

Midirama

Bogotrax

Il Festival Bogotrax è un evento unico nel suo genere, che ha radici profonde nella cultura indipendente e nell’attivismo sociale. Fondato nel 2004, si è affermato come un laboratorio di sperimentazione artistica e sociale, promuovendo la partecipazione attiva e la condivisione delle risorse tra artisti, attivisti e comunità locali.

Ciò che distingue il Bogotrax da altri festival è la sua natura autogestita e il suo impegno per la solidarietà e il lavoro collaborativo. Dal momento della sua fondazione, il festival è stato organizzato da una rete di volontari che lavorano insieme per creare un’esperienza culturale e artistica unica. La sua formula libera e gratuita permette l’accesso a tutti, promuovendo l’inclusione e la diversità.

La musica è al centro dell’esperienza del Bogotrax, ma l’evento abbraccia anche altre forme d’arte e di espressione culturale, come le performance, le proiezioni audiovisive, i workshop e i dibattiti. Questa diversità di contenuti riflette l’importanza della cultura come strumento di trasformazione sociale e di costruzione di comunità.

Le carceri colombiane, come Carcel Distrital, offrono un ambiente unico e complesso per il Bogotrax. Le condizioni difficili e le sfide legate alla vita in penitenziario rendono ancora più significativo l’atto di portare la musica e l’arte all’interno di queste istituzioni. Il festival offre agli internati un’opportunità di connessione e di espressione, creando momenti di gioia e di condivisione in un contesto altrimenti oppressivo.

Con queste prerogative, l’esperienza degli artisti assume un significato particolare, evidenziando il potere trasformativo della musica e il suo ruolo nel creare ponti tra mondi apparentemente distanti. Il Bogotrax diventa così non solo un festival, ma un simbolo di speranza e di resilienza che continua a ispirare e a promuovere il cambiamento nella società colombiana e oltre.

Sistema carcerario colombiano

L’aumento delle violenze sul personale nelle carceri colombiane è un segnale allarmante delle gravi sfide che il sistema carcerario del Paese affronta tutt’ora. La recente dichiarazione di emergenza da parte del governo colombiano è una risposta diretta agli atti di violenza contro il personale dei centri di detenzione in varie località della Nazione.

L’assassinio di una dipendente dell’Istituto nazionale penitenziario e carcerario (Inpec) a Cartagena e l’attacco che ha ferito diversi funzionari nel carcere di Jamundì sono solo due esempi dei gravi incidenti che hanno portato il governo a prendere provvedimenti urgenti.

La dichiarazione di emergenza consente al governo di destinare risorse aggiuntive per affrontare la situazione, comprese misure più efficaci per garantire la sicurezza del personale e dei detenuti. Tra le azioni previste vi è anche la possibilità di bloccare i segnali telefonici all’interno delle carceri, al fine di prevenire la comunicazione non autorizzata tra detenuti e il mondo esterno.

Tuttavia, l’emergenza carceraria è solo un primo passo nel tentativo di affrontare i problemi strutturali e le carenze del sistema penitenziario colombiano. È fondamentale adottare misure a lungo termine per migliorare le condizioni delle carceri, garantire il rispetto dei diritti umani dei detenuti e promuovere la rieducazione e il reinserimento sociale.

La visione di Midirama

Midirama, artista visionario che spinge la sua musica oltre i confini del convenzionale e cattura il pubblico in tutto il mondo con suoni che sfidano i generi. La musica di Midirama funge da connessione fondamentale tra le comunità techno veterane ed emergenti. Midirama è il frutto del lavoro di DJ 4L3R7, noto anche come Disladis, per il suo coinvolgimento nel pionieristico sound system techno libero Cirkus Alien. Le sue produzioni musicali sono sparse tra etichette come Apex Recordings, Berlin Invasion, GrooveCuts, Kiosek Records, Resilient Records e Fatal Noise Records.

Avendo viaggiato per il mondo sia come DJ che con il suo set live, dai piccoli eventi locali ai grandi festival, Midirama di non smette mai di esplorare e continua a ispirare e innovare.

Abbiamo avuto l’opportunità di intervistarlo al ritorno da questa esperienza unica nel suo genere, cercando di comprendere più a fondo che messaggio lancia questa iniziativa.

Cosa ti ha spinto ad accettare l’opportunità di suonare nelle prigioni colombiane durante il festival Bogotrax?

Bogotrax organizza esibizioni nelle prigioni ogni volta che tiene il festival. Quando mandai la mia candidatura quattro anni fa, volevo partecipare e già facevo parte del festival, ma tra i tanti DJ presenti al festival, solo un numero molto limitato ha avuto l’opportunità di vivere questa esperienza. Quest’anno, ho presentato nuovamente la domanda per far parte di questo evento e sono stato scelto. C’erano due DJ del sound system che hanno suonato lì, un DJ di Bogotà, un DJ del Messico, un MC francese e io.

Come ti sei preparato mentalmente ad affrontare un ambiente così specifico e complesso come una prigione?

Non avevo idea di cosa aspettarmi. È utile menzionare che non parlo spagnolo. La gente mi ha detto che avrebbero voluto tutto quello che avevo con me lì. Alla fine, nonostante i controlli rigorosi, non ho potuto portare nemmeno una felpa con cappuccio, una cintura, un orologio, un telefono, ecc. Avevo solo una chiavetta USB con la musica e delle cuffie, pantaloni che mi cadevano, e sotto la maglietta avevo messo un’altra maglietta perché volevo darla a qualcuno lì. Ero più preoccupato su cosa avrei dovuto suonare, se qualcosa di più locale, ma mi è stato detto che ero l’unico DJ techno lì e che avrei suonato più veloce, quindi non dovevo preoccuparmi troppo. Beh, alla fine, è stata davvero un’esperienza unica, devo ammettere.

Quali sono state le tue prime impressioni quando sei entrato in prigione? Cosa hai provato?

Ho sentito una grande tensione. Le guardie erano piuttosto antipatiche; per loro era solo un lavoro in più. Non prestavano molta attenzione a noi. Abbiamo dovuto passare attraverso diversi controlli, dare le impronte digitali, sottoporci ai controlli dei cani, dove li spingevano davvero a annusarci il più possibile, c’erano telai, sedie per la scansione. Quando ho visto i primi detenuti in uniforme arancione, mi è caduta addosso una tensione ancora maggiore. E in cima a tutto ciò, dovevamo trasportare quei grandi altoparlanti e attrezzature lì, quindi potevamo anche suonare del tutto.

Durante il tuo set, quali sono stati i momenti più significativi o emozionanti che hai vissuto?

Durante questo evento, le donne erano al piano terra e gli uomini sui balconi ai piani superiori. Prima della mia esibizione, le guardie hanno mandato via le donne, dicendo che era finita – si avvicinava l’ora di pranzo. Ero piuttosto triste per questo e non sapevo nemmeno se avrei mai suonato. Ma quando ho iniziato a mettere su la prima traccia, le guardie hanno aperto i cancelli per gli uomini ai piani superiori, che si sono immediatamente precipitati giù e hanno creato una folla incredibile intorno al palco. Giovani e anziani. Nessun grande trambusto, solo molto saltare, agitare le mani e gridare – un vero e proprio mosh pit, ti dico.

Come hai percepito la reazione e la partecipazione dei detenuti alla tua musica e alla tua presenza?

Immagina di essere rinchiuso per forse 10 anni. Giorno dopo giorno, è sempre lo stesso, tutto grigio, e improvvisamente bam! C’è questo circo in corso. La gente era emozionata solo dal fatto che stesse succedendo qualcosa. E per coloro che amavano la musica, se la stavano godendo. Anche sui piani superiori, abbiamo visto persone che facevano un vero e proprio allenamento – voglio dire, ballavano come se fosse la fine del mondo, alcuni stavano solo osservando. Ma c’era questo ragazzo che faceva breakdance incredibilmente bravo, o una ragazza che prendeva in prestito un microfono e faceva un freestyle, poi altri due ragazzi.

Qual è stata la tua principale motivazione nel partecipare a un progetto così importante come Bogotrax? Puoi raccontarci di più sulle persone e le organizzazioni dietro a tutto ciò?

Bogotrax mi ricorda la cultura europea della musica techno libera. Le persone lo organizzano senza chiedere alcun compenso, proprio come gli artisti. Perché in Colombia il divario tra ricchi e poveri è molto ampio, ci sono molti giovani che non hanno l’opportunità di andare alle feste nei club. Invece al Bogotrax possono partecipare a tutte le feste, mostre, workshop gratuitamente. Penso che sia molto importante che queste persone lo organizzino lì. In Colombia non hanno neanche il diritto di ricevere alcun finanziamento per questo. Ma per fortuna gli organizzatori hanno un cuore grande!

A livello personale, cosa porti con te dopo aver vissuto questa esperienza nelle prigioni? Cosa hai imparato da questa esperienza?

Ho realizzato ancora di più quanto sia importante apprezzare le cose ordinarie che comunemente consideriamo normali – come poter camminare per strada, esporre il viso al sole, bere una birra da qualche parte, dare un bacio a una bella ragazza. Dovremmo essere grati per tutte queste cose ordinarie. E lo sono!

Alla luce di questa esperienza, come pensi che la musica e la cultura possano contribuire a portare cambiamenti positivi nei contesti carcerari e nella società nel suo complesso?

So che in alcune prigioni della Repubblica Ceca ai detenuti è consentito formare gruppi musicali o partecipare ad attività musicali, o addirittura fare alcuni lavori di produzione. Coloro che suonano non si comportano male. Durante il mio viaggio in Colombia, ho letto un libro straordinario di Jack London chiamato “Star Rover“, il che mi ha portato a riflettere di più su quanto sia efficace una punizione come la detenzione o l’esecuzione, o piuttosto, tutto ciò è terribilmente individuale.

Credi che lo stile musicale, in particolare la musica techno, abbia un potere particolare nel connettere le persone, specialmente in contesti come le prigioni? Perché?

La musica techno è più tribale; i ritmi ripetitivi sono radicati in noi dai tempi in cui ballavamo intorno al fuoco al suono dei tamburi. Tuttavia la musica in generale unisce le persone. È un linguaggio universale – e poi dicono che l’abbiamo perso con la costruzione della Torre di Babele (ride, ndr).

Hai avuto l’opportunità di interagire con i detenuti prima o dopo il tuo set?

Quando ho finito, abbiamo dovuto spegnere tutto e cominciare a imballare. Sono venuti da noi e ci hanno ringraziato molto, chiedendomi perché fossi venuto a suonare per loro. Ho firmato tovaglioli, pelli, le loro uniformi carcerarie. Erano davvero grati, sono rimasto assolutamente commosso, non mi aspettavo una risposta del genere.

Infine, pensi che esperienze come questa possano avere un impatto duraturo sulla tua musica e sulla tua carriera artistica? Come pensi che influenzerà il tuo futuro lavoro?

Non penso che avrà un impatto sulla mia musica, anche se chi lo sa, ogni umore di qualsiasi creatore ha un’influenza. Dall’esibizione in prigione rifletto di più sulla libertà personale e su cosa significhi effettivamente. Sono grato per tutte le cose che posso fare e per quello che ho nella vita. Mi rendo conto che non ho bisogno di così tante delle cose davvero importanti, e sto riducendo al minimo la mia vita e le cose intorno a me. Coltivo l’amore per la vita e per la musica.

La musica elettronica come strumento di cambiamento sociale

Arrivati a questo punto è importante riflettere sul significato più profondo di tali atti di altruismo e creatività in contesti così difficili come le carceri colombiane. Questi artisti hanno dimostrato il potere della musica e dell’arte come strumenti di cambiamento sociale e di guarigione, offrendo un’opportunità di connessione e di espressione per i detenuti.

L’esperienza di suonare nelle carceri non è stata solo un atto di intrattenimento, ma una dimostrazione tangibile di solidarietà e di umanità. In un ambiente oppressivo e spesso privo di speranza, la musica ha rappresentato un raggio di luce, offrendo ai detenuti un momento di gioia e di libertà attraverso la creatività e la condivisione.

La musica e l’arte possono essere potenti strumenti di cambiamento sociale, in grado di promuovere la consapevolezza, l’empatia e la comprensione reciproca. Attraverso iniziative come il Bogotrax, è possibile creare spazi inclusivi e accessibili dove le persone possono esprimersi liberamente e connettersi con gli altri, superando le barriere fisiche e sociali che talvolta sembrano insormontabili.

Midirama torna live in Italia per due date imperdibili insieme a SUM – Sound Underground Music: il 20 aprile 2024 per il secondo appuntamento di RESONANCE con Insane Teknology, Oby One, Adrian Effe e Teknotronik allo SpazioDora di Torino e l’11 maggio 2024 a Roma per Revolution Culture insieme a AN ON BAST, Francesco Zappalà, Oscar Aurino, The Violinist e T. Lorenz, per maggiori info QUI.

Credit photo Manuela Uribe

Leggi anche : Support The Sound: come sostenere (concretamente) i producer?

ENGLISH VERSION

Midirama : “With Bogotrax, we took techno to Colombian prisons”

Midirama’s words, one of the protagonists of the Bogotrax festival, describe a unique and intense experience, symbolizing an incredible fusion of music, art, and social commitment. But this is not just his story. It’s a testimony of how music can transcend physical and mental boundaries, bringing hope and connection even in the darkest and most oppressive places.

Midirama, along with other artists like El Gran Latido, Fufu, Baptiste, Seppuku and Rach, crossed the gates of the prison to bring his music and his message of solidarity to the inmates of Carcel Distrital. But behind this entertainment mission, there is much more: there is the will to break down barriers between people, to share moments of joy, and to recognize the humanity in those who are often forgotten by society.

In the editorial that follows, we will explore the experiences of one of the DJs present, delving into his emotions, challenges, and hopes. Through Midirama’s story, we will discover the transformative power of music and the importance of keeping the flame of creativity alive even in the darkest places. Welcome to a journey inside the walls of the prison, where techno music becomes a bridge to freedom and rebirth.

“February 2024, Bogotá, Colombia: Here are the promised photos from playing in the Colombian prison.I got up at 6 am(after returning late from the street party)and met the others outside the prison where El Gran Latio Soundsystem was already laid out. To get inside, we had to hand over everything, I couldn’t even have a belt or a hoodie, just headphones and a USB stick. Followed by a thorough search, metal detectors, and sniffer dog, adding to the oppressive atmosphere. After the relocation and setting up of the soundsystem, chaos ensued at the first position, so the action had to be moved to the adjacent block. There, women were brought downstairs. We witnessed some good breakdancing, freestyling on the mic by girl and guys. The mood, besides the great DJs, was hyped by MC Baptiste. I played last, and before the women were taken away, they opened the gates, and the men from the upper floors crowded around the decks, creating a proper frenzy. We were all jumping. During the set, I gave my shirt to the crowd—a civilian commodity highly appreciated there. My set was short but intense. At the end, everyone wanted to thank and shake hands—young and old alike. We left knowing we were going out, but some of them would still be in there for many years. Outside, I took a deep breath and headed towards new adventures at Bogotrax”

Midirama

Bogotrax

The Bogotrax festival is a unique event deeply rooted in independent culture and social activism. Founded in 2004, Bogotrax has established itself as a laboratory for artistic and social experimentation, promoting active participation and resource sharing among artists, activists, and local communities.

What sets Bogotrax apart from other festivals is its self-managed nature and its commitment to solidarity and collaborative work. Since its inception, the festival has been organized by a network of volunteers working together to create a unique cultural and artistic experience. Its free and open formula allows access to all, promoting inclusion and diversity.

Music is at the heart of the Bogotrax experience, but the festival also embraces other forms of art and cultural expression, such as performances, audiovisual projections, workshops, and debates. This diversity of content reflects the importance of culture as a tool for social transformation and community building.

Colombian Prison System

Increase in violence against personnel in Colombian prisons is an alarming sign of the serious challenges facing the country’s prison system. The recent declaration of a prison emergency by the Colombian government is a direct response to acts of violence against detention center staff in various locations across the country.

Murder of an employee of the National Penitentiary and Prison Institute (Inpec) in Cartagena and the attack that injured several officials in the Jamundì prison are just two examples of the serious incidents that have prompted the government to take urgent action.

The declaration of an emergency allows the government to allocate additional resources to address the situation, including more effective measures to ensure the safety of staff and inmates. Among the planned actions is also the possibility of blocking phone signals inside prisons, in order to prevent unauthorized communication between inmates and the outside world.

However, the prison emergency is only a first step in addressing the structural problems and shortcomings of the Colombian prison system. It is essential to adopt long-term measures to improve prison conditions, ensure respect for the human rights of detainees, and promote rehabilitation and social reintegration.

Introducing Midirama

Introducing Midirama, a visionary artist pushing the boundaries of sonic exploration and captivating audiences worldwide with mesmerizing beats and genre-defying soundscapes. Midirama’s music transcends boundaries and defies expectations, serving as a core intergenerational connection between veteran and emerging techno communities. MIDIRAMA is the brainchild of DJ 4L3R7, also known as Disladis for his involvement with the free technopioneering Cirkus Alien soundsystem. His music releases are scattered across Apex Recordings, Berlin Invasion, GrooveCuts, Kiosek Records, Resilient Records, and Fatal Noise Records. Having traveled the world both as a DJ and with his live set, from local events to major festivals, Midirama’s never-stop-exploring attitude continues to inspire and innovate.

We had the opportunity to interview Midirama upon his return from this uniquely genre-defying experience, seeking to gain a deeper understanding of the significant message that this initiative conveys.

What prompted you to accept the opportunity to play in Colombian prisons during the Bogotrax festival?

Bogotrax organizes performances in prisons every time they hold the festival. When I attended Bogotrax four years ago, I wanted to participate, but out of the huge number of DJs at the festival, only a very small number had the opportunity to undergo this experience. This year, I applied again to be part of this event, and they chose me. There were two DJs from the soundsystem that played there, one DJ from Bogota, one DJ from Mexico, an MC from France, and me.

How did you mentally prepare to face such a unique and complex environment as a prison?

I had no idea what to expect at all. It’s worth mentioning that I don’t speak Spanish. People told me that they would want everything I had on me there. In the end, despite strong controls, I couldn’t even take a hoodie, belt, watch, phone, etc. I only had a USB drive with music and headphones, pants that were falling off me, and under my shirt I had taken another T-shirt because I wanted to give it to someone there. I was more concerned about what I should play, whether something more local, but I was told that I was the only techno DJ there and that I would play the fastest, so I shouldn’t worry too much about it. Well, in the end, it was quite a ride, I have to admit .

What were your first impressions when you entered the prison? What did you feel?

I felt a great tension. The guards were quite unpleasant; for them, it was just extra work. They didn’t pay much attention to us. We had to go through several checks, give fingerprints, undergo dog checks, where they really urged them to sniff us as much as possible, there were frames, chairs for scanning. When I saw the first inmates in orange uniforms, an even greater tension fell upon me. And on top of that, we had to move those huge speakers and equipment there, so we could even play at all.

During your set, what were the most significant or exciting moments you experienced?

During this event, women were on the ground floor and men were on the balconies on the upper floors. Before my performance, the guards sent the women away, saying it was over – lunchtime was approaching. I was quite sad about this and didn’t even know if I would still play. Nevertheless, I went to play, and the guards opened the gates for the men on the upper floors, who immediately rushed down and created an incredible crowd around the DJ booth. Both young and old No big fuss, just a lot of jumping, waving hands, and shouting – a proper mosh pit, I tell you.

How did you perceive the reaction and participation of the inmates to your music and presence?

Imagine being locked up for maybe 10 years. Day in and day out, it’s the same, all gray, and suddenly bam! You have this circus going on. People were excited just that something was happening. And for those who loved music, they were enjoying it. Even up on the upper floors, we saw people doing a proper workout – I mean, they were dancing like it was the end of the world, some were just observing. But there was this guy who did an incredibly good breakdance, or one girl who borrowed a microphone and did a freestyle, then another two guys.

What was your main motivation in participating insuch an important project like Bogotrax? Can you tell us more about the people and organizations behind this great project?

Bogotrax reminds me of the European free techno culture. People organize it without claiming any fee, just like the performers. Because in Colombia, the gap between the rich and the poor is very wide, there are many young people who don’t have the opportunity to go to parties in clubs. Not at Bogotrax – during it, they can attend all parties, exhibitions, workshops for free. I think it’s very important that these people organize it there, and in Colombia, they don’t even have the right to receive any grant for it. The orgs are big-hearted!

On a personal level, what baggage did you bring with you after experiencing this in the prisons? What did you learn from this experience?

I realized even more how one should appreciate ordinary things that we commonly consider normal – like being able to walk down the street, expose your face to the sun, have a beer somewhere, give a kiss to a beautiful girl. We should be grateful for all these ordinary things. And I am!

In light of this experience, how do you think music and culture can contribute to bringing about positive changes in prison contexts and society as a whole?

I know that in some prisons in the Czech Republic, inmates are allowed to form bands or engage in music activities, or even do some production work. Those who play do not misbehave. On my way to Colombia, I read an amazing book by Jack London called “Star Rover” – which led me to think more about how such punishment as imprisonment or execution is ultimately effective, or rather, all this is terribly individual.

Do you believe that the musical style, particularly techno, has a particular power in connecting people, especially in contexts like prisons? Why?

Techno music is more tribal; repetitive beats are rooted in us from the times when we danced around the fire to the sound of drums. Nevertheless, music in general brings people together. It’s a universal language—and then they say we lost it with the construction of the Tower of Babel, haha.

Did you have the opportunity to interact with the inmates before or after your set? If so, what were their reactions and feedback?

When I finished, we had to turn everything off and start packing up. They came up to us and thanked us a lot, asking me why I came to play for them. I signed napkins, skin, their prison uniforms. They were really grateful for it, I was absolutely touched, I didn’t expect it to have such a response.

Finally, do you think experiences like this can have a lasting impact on your music and artistic career? How do you think it will influence your future work?

I don’t think it will have an impact on my music, although who knows, every mood of any creator has an influence. Since the performance in prison, I reflect more on personal freedom and what it actually means. I am grateful for all the things I can do and what I have in life. I realize that I don’t need so many of the really important things, and I’m quite minimizing my life and things around me. I cherish love for life and music.

Electronic Music as a Tool for Social Change

At this point, it is important to reflect on the deeper meaning of such acts of altruism and creativity in such difficult contexts as Colombian prisons. These artists have demonstrated the power of music and art as tools for social change and healing, offering an opportunity for connection and expression for inmates.

The experience of playing in prisons was not just an act of entertainment, but a tangible demonstration of solidarity and humanity. In an oppressive and often hopeless environment, music represented a ray of light, offering detainees a moment of joy and freedom through creativity and sharing.

Music and art can be powerful tools for social change, capable of promoting awareness, empathy, and mutual understanding. Through initiatives like the Bogotrax festival, it is possible to create inclusive and accessible spaces where people can express themselves freely and connect with others, overcoming physical and social barriers that sometimes seem insurmountable.

Midirama’s coming back live to Italy for two must-see gigs with SUM – Sound Underground Music: April 20, 2024, catch them at the second RESONANCE event with Insane Teknology, Oby One, Adrian Effe, and Teknotronik at SpazioDora in Turin. Then on May 11, 2024, they’re hitting up Rome for Revolution Culture alongside AN ON BAST, Francesco Zappalà, Oscar Aurino, The Violinist, and T. Lorenz. Get more details HERE.

Credit Photo Manuela Uribe